Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

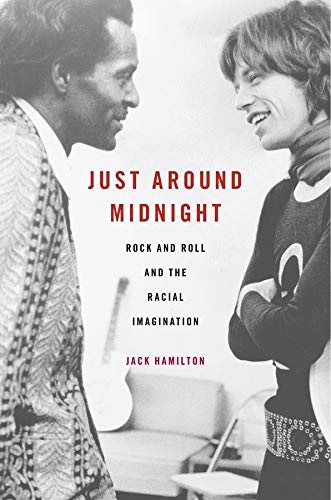

Just around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

D**D

It's Complicated

The subject matter of this book is complicated. It follows the development of rock and roll from black music to white ownership. Race and music are intertwined, this books attempts to unravel that intertwining. It is well researched and has numerous footnotes from source material. Listening to the music used as examples in the book can help in understanding the points made by the author.

D**E

Tired Arguments, Stuffy Writing

Given the potent thesis Jack Hamilton gives himself in “Just Around Midnight,” one wonders why he artificially limits his study of the racial imagination via popular music to the 1960s. There is far too much that Hamilton leaves out in his 10 year study, but if he is limited to a decade, I wonder why 1965 to 1975 wasn’t more appealing to him, given the extreme whiteness of prog rock, the extreme racism of southern rock, and the extreme innovations of funk, hip hop and R&B. To strictly cut himself off at 1970 denies the reader much of the fluidity of race and music that Hamilton spends his whole book trying to get us to see.Hamilton’s background is as a pop culture writer for Slate, so I was ready for the very redundant double-standard arguments that make most of the book, arguments that anyone smart enough to choose this book already knows plenty about. The book’s structure is composed of juxtapositions between popular black and white artists and their songs. This model feels rather prescriptive and works against the complex point he’s trying to make about these artists’ interracial and mutually inspiring backstories. For example, Hamilton justifies a chapter comparing Bob Dylan with Sam Cooke because of their “assaults on form and genre,” “defections from the musical communities they came from,” and their “artistic autonomy.” These seem to be hallmarks of any great musician of the 60s. One wonders if Hamilton could’ve just as easily compared Ray Charles with Frank Zappa, or Aretha Franklin with David Bowie.Third, and most important, is the last thing any progressive academic wants to hear: Hamilton is employing the same myopia and narrow-mindedness his work is seeking to address. Why does he isolate the genius of Dylan in a racial context, yet cherrypick the violence of Hendrix and race-centric Stones as more of an embodiment of race. I’d argue that Hendrix is fare more the more exceptional and groundbreaking genius than Dylan was. Or why does Hamilton have a whole chapter on ‘rock criticism’ and not devote a chapter to the African American intellectual culture at the time? Also, Hamilton is indeed cautious enough to not limit his book to the accusations of racial binary (i.e., only mentioning black and white contributions to rock music), so he tokenistically mentions Carlos Santana, but it’s more to cover his bases than to paint the rainbow of rock. Speaking of rainbows, if you’re looking for the deeper layers of white dominant culture pillaging other social groups, and the intersectional nature of such interactions, like with LGBT culture (Little Richard, Billy Preston, Bowie) and rural white culture (i.e. The Stones’ interest in country, The Allman Brothers band) look elsewhere. This book plays the same binary tune for 270 pages. While confined white/black study might be Hamilton’s interest, it unfortunately loses ours.In terms of the writing itself, it’s dressed in the stuffy thinkpiece jargon that you’ve come to dread when reading Slate (e.g. “differentness”, “indices,” “hegemonic white masculinism”). Some sentences are so overwritten, you lose track of whether he’s really proving what he’s trying to say. Also, Jack Hamilton-the-Musician shines through in dozens of pages throughout the book in which he discusses the chords and keys of songs, thus making large swaths of the book mean absolutely nothing to the non-musician.Nevertheless, there are some interesting gems for those looking for obscure facts for the next dinner party. You’ll surely impress with your new knowledge of Motown’s influential bassist, James Jamerson. Or the well-researched British subcultures leading up to the British Invasion in the book will fascinate. But if you’re looking for a book that really offers diamond after diamond in rock’s rough, you’ll have to look elsewhere. For such a powerful topic, this is a rather pretentious and milquetoast book conjuring up the same tired devices, and leaving the reader with “it was a lot more complex” without showing us how.

B**N

So much of popular music in the US revolves around ...

So much of popular music in the US revolves around how listeners and musicians make sense of a defining conflict in American society: race. Hamilton shows how this played out in the production of some of the most memorable music in the country's recorded history. Fantastically written, with astounding new facts and insights about artists and songs you thought you knew. Made me listen to Gaye, Cooke, Dylan, and The Beatles, amongst others, as if for the first time.

E**R

thought-provoking and well-written book

This book exposes a very interesting aspect of cultural history -- how rock and roll went from black to white. It's well written, full of examples that indicate the author's deep knowledge of the music and the times. Would be of special interest to those aging Boomers who lived through it all!

F**A

Excellent

A study in white appropriation of black music and, in turn, of African America's legacy in American popular music. A great read. Highly recommend!

S**E

Three Stars

received as advertised. would buy again from seller

C**N

Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

I stumbled upon JUST AROUND MIDNIGHT: ROCK AND ROLL AND THE RACIAL IMAGINATION (Harvard University Press, 2016) while perusing Tantor Audio's huge list of audio books. Here's the blurb that drew my attention:Rooted in rhythm-and-blues pioneered by black musicians, 1950s rock and roll was racially inclusive and attracted listeners and performers across the color line. In the 1960s, however, rock and roll gave way to rock: a new musical ideal regarded as more serious, more artistic-and the province of white musicians. Decoding the racial discourses that have distorted standard histories of rock music, Jack Hamilton underscores how ideas of "authenticity" have blinded us to rock's inextricably interracial artistic enterprise.I requested the book thinking it might inform my novel, Half-Truths. To be honest, it was a scholarly (yet accessible) work that far exceeded my expectations. All it lacked were snippets from the multitude of songs and albums the author referenced.I grew up in the 60's singing to the music coming from my father's transistor radio. I had no idea the cultural interchanges between white and black cultures that went on behind the scenes producing the lyrics I sang. I also did not know the personal life stories of the musicians. The author's extensive research and knowledge of music created a rich backdrop for this tumultuous time period.Here is just a sprinkling of the issues Hamilton addressed that I never considered as a teeny bopper listening to music at our neighborhood pool.Racial roots ran deep for the music that was popular in the 50's and 60's.Blacks felt as if their music was plundered involving issues of cultural ownership and racial authenticity.Hamilton traced the roots of 60's rock and roll back to the King of Soul, Sam Cooke, who he juxtaposed with Bob Dylan, the leader of the folk rock movement.Gospel music, slavery songs, civil rights, the southern freedom struggle and political unrest all influenced music. Similarly, there was dynamic back-and-forth movement as music itself influenced politics and culture.Protests against capitalism made big bucks for record companies. (Think of musicians in the 60's such as Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, and of course, Bob Dylan himself.)Music was made to be danced to and sold.Performance and identity are intertwined for many musicians.The term "invasion" should not have described the Beatles. There were tons of influences on the Beatles from this side of the Atlantic including Motown and Cuban music. Other influences included British blues (itself derived from American blues), Keith Richards, Tads, Skiffle.White artists performed black songs and vice versa. For example, both Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder sang Bob Dylan's songs. Aretha Franklin (the Queen of Soul), Janis Joplin (the Queen of Rock), and Dusty Springfield sang each other's music. Joplin sang black music in white-only venues; Franklin sang the Beatles, "Eleanor Rigby" in first person and made it into a rhythm and blues rendition that Hamilton called "audacious" and "genre bending". Hamilton went into great depth analyzing how each musician's rendition made a song his or her own and their motivation to assimilate the music into his/her own repertoire.What is soul? In Hamilton's words, "Soul is a way to think about race." According to some commentators at the time, "to have soul was to suffer unjustly at hands of whites."Do whites have the ethical right to play black music? If not, isn't this racism? The problem was that whites got paid more for their performances.There were musical commonalities between the Beatles and Ray Charles. Ideas of what white and black musicians can and cannot do, rarely hold up to scrutiny of musical practice.Often Jimmy Hendrix expressed his dismay at the Vietnam War through musical violence. To him, it was a critique of the society around him. But derogatory remarks made about him among critics often marked him as "other".The Rolling Stones were obsessively grounded in black roots.The narrator, Ron Butler, did an excellent job. I could listen to him read any book! Here is a sample from MIDNIGHT. If you are interested in delving into the cultural and musical environment of the 50's-early 70's, then this is a book for you.I'm giving away the MP3-CD that I received from Tantor Audio. It is encoded in MP3 format and is iPod ready but will play only on CD and DVD players or computers that have ability to play MP3 formatted disks. (That meant I could play it in one of our cars but not the other and it didn't work on an old CD player.) Please leave your email address if you are new to my blog. Giveaway ends June 2, 2017.

S**O

Ségrégation musicale

Je ne sais plus comment je suis arrivé à apprendre l'existence de ce livre (je suspecte une recommandation d'amazon) mais son interrogation principale a retenu mon attention : qu'est-ce qui a fait qu'un genre de musique né du croisement de musiques créées par des musiciens noirs autant (sinon plus) que de musiciens blancs est aujourd'hui (et depuis longtemps) massivement perçue comme une "musique de blancs" ?Le fait que cette question soit abordée par un auteur étatsunien était pour moi un plus, le rock étant une création des USA, avec une aide déterminante des anglais, que ce livre n'oublie pas.L'auteur, Jack Hamilton, est un universitaire, aujourd'hui maître assistant au sein du département d'étude des média de l'université de Virginie. "Thirty-something", Hamilton est né et a grandi dans la région de Boston et, près avoir travaillé professionnellement en tant que musicien pendant quelques années, il a passé un bachelor of arts en Anglais à l'université de New York en 2003, et a ensuite préparé et obtenu en 2013 un doctorat en "American Studies" à Harvard.Ce premier livre est le résultat de plusieurs années de recherches et regroupe la matière de plusieurs travaux précédents.Cet ouvrage, qui est son premier livre, présente six points spécifiques d'observation historique qui, via une analyse minutieuse, révèle les mouvements à l'oeuvre aux USA (mais aussi en Angleterre) dans les années 1960 (et un peu avant) pour qu'au final, lorsque l'on évoque le "classic rock" des années 1970 et le rock des années suivantes (même "indé"), les musiciens afro-américains soient totalement absents des bacs à disques.Un premier chapitre aborde les destins croisés au tout début des années 1960, de Sam Cooke et de Bob Dylan. Le premier, jeune star de la scène gospel, se mue en star de la musique soul mais aussi pop en même temps qu'il se lance dans le business. Il doit faire face à des critiques de tous bords mais qui on pour point commun une accusation plus ou moins marquée de trahison puisqu'il abandonne le gospel, puis - selon certains - la musique noire en écrivant des hits pop et en chantant dans des endroits fréquentés par la bourgeoisie blanche (le "Copa"), sans compter la dimension entrepreneuriale. Cooke écrira la chanson 'A Change Is Gonna Come', son chef d'oeuvre, sur inspiration de 'Blowin' In The Wind' de Bob Dylan. Ce dernier, de même, sera accusé de trahison pour être passé au "folk-rock" (pour ne pas dire carrément au rock) alors même qu'il s'est toujours réclamé de Little Richard et qu'il jouait du piano dans des groupes rock'n'roll avant de se convertir à Woody Guthrie. Au passage, Bob Dylan contribuera fortement à montrer que le rock n'est pas une mode et il inventera (à son corps défendant) le "rock adulte" ou le "rock moderne".Cooke autant que Dylan seront l'objet d'injonctions contradictoires alimentées en particulier par les grands médias, les maisons de disques et la presse spécialisée (cf. en particulier le Billboard et ses hit-parades).Le chapitre suivant aborde la "British Invasion" vécue par les USA avec l'arrivée des Beatles puis d'un ensemble de groupes anglais, les Rolling Stones parmi eux. L'auteur montre qu'il n'y a pas vraiment eu "invasion britannique" des USA et que les îles britanniques avaient eu elles aussi à "subir" des invasions étatsuniennes. Hamilton évoque longuement les "trads", les "teds" et le skiffle. "Trads" et "Teds" donnent aussi dans les injonctions paradoxales. Les "trads" vénèrent la musique jazz afro-américaine du milieu du siècle mais considèrent le "bop" - la musique jazz du moment -, comme quantité négligeable. A leur suite, les fans de blues auront tendance à se poser en "puristes" et à préférer des artistes morts ou retraités à la musique afro-américaine dominante du moment, plutôt R&B et soul, qui est une trahison. Les "teds" adorent le rock'n'roll mais sont très conservateurs et aussi plutôt racistes. Quant au skiffle, c'est d'abord plus cette musique qui a généré tout un engouement des jeunes britanniques au milieu des années 1950 que le rock'n'roll lui-même. A nouveau, les musiciens afro-américains du moment sont plutôt négligés, sauf exception (cf. le travail d'Alexis Korner etc.).Particulièrement intéressant, le troisième chapitre souligne l'influence de la musique afro-américaine sur la musique des Beatles, montrant que les Beatles - contrairement à ce qui est souvent soutenu - sont moins des paragons du rock blanc à vélléités symphoniques que des musiciens à l'écoute de ce qui se passait en particulier du côté de la Motown et notamment de son bassiste génial James Jamerson. Hamilton étant musicien, il propose quelques comparaisons de tablatures à l'appui. Inversement, des artistes afro-américains se sont appropriés sans difficulté apparente des chansons des Beatles telles que "Eleanor Rigby" ou "Yesterday".L'auteur consacre ensuite tout un chapitre à trois chanteuses majeures des années 1960 : Janis Joplin, Aretha Franklin et Dusty Springfield. Le fond de la question est ici : "qu'est-ce que chanter "soul" et qui a le droit ou pas de chanter "soul" "? Janis Joplin copiait-elle les chanteurs et chanteuses afro-américain(e)s ou bien extériorisait-elle son "âme" ? Et, avec quasiment les mêmes musiciens, qui a le mieux chanté "Son of A Preacher Man" ? 'Re ou Dusty ?Tout un chapitre est ensuite consacré à Jimi Hendrix, qui était il y a 50 ans un "OVNI" et qui, à bien des égards, le reste aujourd'hui. Hendrix, au cours de sa courte vie de "band leader", a passé son temps à innover, bien loin des manières de penser blanches ou noires, créant de toutes pièces une musique nouvelle dont une partie donnera le hard-rock et le heavy metal. Jusqu'à Prince, Hendrix a longtemps été l'exception qui confirme la règle : le seul artiste afro-américain à figurer dans les bacs à disques "rock moderne".Le dernier chapitre traite des Rolling Stones, ce groupe britannique qui a tout le temps cité ses inspirations et sources afro-américaines (Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Chess Records etc.), a longtemps refusé l'étiquette "rock'n'roll" pour finalement devenir nolens volens le plus grand groupe de rock du monde. Hamilton s'arrête sur la reprise de 'Not Fade Away' (qui redonne à Bo Diddley ce que la reprise de Buddy Holly avait mis de... Buddy Holly), sur 'Satisfaction' et ses reprises par Otis Redding et Aretha Franklin, puis sur 'Jumpin' Jack Flash' et 'Gimme Shelter'. Malgré tout le discours du groupe sur les musiques qui l'inspirent, au-delà des premières parties - qui ont notamment mis Ike & Tina en lumière auprès du grand public -, les Stones restent massivement perçus comme un groupe "rock". Une vision que peut-être leur dernier album en date, composé intégralement de reprises de vieux blues - vise à redresser.S'il s'agit indubitablement d'un travail universitaire, le livre se lit relativement facilement, notamment bien sûr si on s'intéresse au rock, au blues, à la soul music etc. En fin d'ouvrage sont regroupées toutes les notes qui auraient pu figurer en bas de page au fur et à mesure ainsi que les très nombreuses et variées sources de l'auteur. La manie de coller des étiquettes, les préjugés, les stratégies commerciales, le racisme plus ou moins latent sont bien entendu en filigrane de cette évolution qui en quelques années a passé Chuck Berry et ses successeurs afro-américains aux oubliettes.

A**E

Geschenkoption

Schönes Buch, was als Geschenk hoffentlich den Nerv des Beschenkten trifft. Für Musikbegeisterte sicherlich sehr geeignet und auch wenn auf es auf Englisch ist gut verständlich!

Trustpilot

3 days ago

2 weeks ago