Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

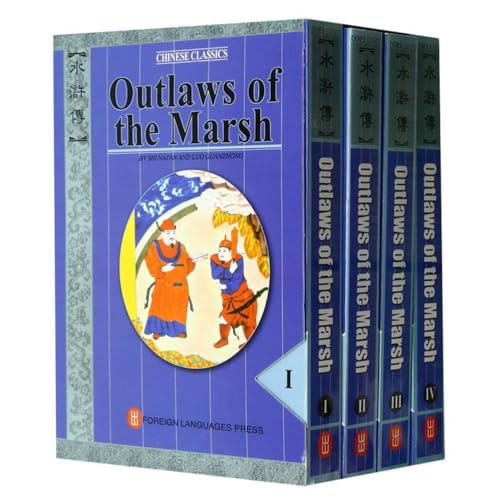

Buy Outlaws of the Marsh (The Water Margin), Translated By Sidney Shapiro, 4 Volume Complete Set in Slipcase by Shi Nai'an, Luo Guanzhong, Syney Shapiro from desertcart's Fiction Books Store. Everyday low prices on a huge range of new releases and classic fiction. Review: A lot more than a yarn about robbery with violence - Two things you notice about this novel are: first, you get four volumes totalling over 2100 pages in a slip case; second, each volume is perfectly sized for a laptop case or pocket or handbag. So, the formatting would have been perfect if I had still been commuting. As it was, I read all four volumes during the Co-vid lock down and semi-lock down, and had a wonderful sense of escapism, as I spent several weeks in 12th century China. Older readers might remember the TV series The Water Margin, which feels as if it was shot soon after Outlaws of the Marsh was written in the 14th century. The book is far longer and more complicated than the series, although this edition might still not give you the full monty. In the introduction, a professor of Chinese literature, Shi Changyu, explains that the novel exists in several different versions, varying between 70 and 124 chapters. This edition has 100 chapters, which might be a good compromise. At the end the translator, Sidney Shapiro, explains how he put this edition together, selecting bits from the short and long editions, and excluding some ridiculous poems that give away the plot. Shapiro himself was an American who lived in China for many years, married a Chinese woman and became a Chinese citizen in 1963, just in time for the Cultural Revolution. I wonder what Mao thought of this novel. The translation itself was made in the 1970s, and gives us a lively, colloquial read which “zips along” – just like a recent Booker Prize judge said novels ought to do. The text itself is an odd mixture of American and British grammar and spelling, with lots of typos, but that don’t detract from the enjoyment of the read. So, what’s it all about? The novel was written in the 14th century and is based on real events that occurred in the 12th century. In some ways it’s a kind of Robin Hood story. 108 men and women (if memory serves, 105 men and three women) are obliged, through a combination of injustice and misfortune, to betake themselves to Liangshan Marsh where they join a growing robber band that robs the rich and either gives to the poor or leaves the poor alone. The 108 chieftains (there are thousands of foot soldiers in the band) are all distinct characters, and along with their given name, they each have a moniker that reflects some feature of their history, physique or chosen weaponry. For instance, one of the female chieftains is called Ten Feet of Steel because she wields two swords, both five feet long, to deadly effect. The first couple of volumes tell the story of each of the chieftains and how they came to join the robber band. They spend a lot of time consuming vast quantities of wine (presumably rice wine) and meat in taverns that seem to be strewn around the countryside. It’s so easy to walk into a tavern and demand a bowl of wine and a platter of meat, but do you always know what you’re getting? There are a lot of rascally inn-keepers who drug their guests and then take them to an abattoir round the back of the tavern where they chop them up and cook them in pies which they serve the next set of guests. No food safety standards in 12th century China. Eventually the emperor realises that the bandits are a potential force for good and after a couple of attempts to offer them an amnesty are thwarted by evil, envious officials, they go mainstream and are used to fight against neighbouring kingdoms. Warning: there is a lot of violence throughout the novel, but it often feels like cartoon violence. Lots of heads are chopped off and bodies salami-sliced, but there is little graphic description and most of the victims are nasty people who deserve a bit of rough justice. There is enough moral philosophy around to raise this novel above a mere adventure yarn, with frequent references to Buddhism, Taoism, filial piety and the sanctity of friendship and oaths. Another warning, which is stated in the introduction, is that women do not get a good press here. Apart from the female chieftains (and they’re not really central characters) most of the female characters are grasping wives who cheat on their husbands, bawds who facilitate adultery or ale-wives who drug their guests and bake them in pies. I won’t spoil the ending. Suffice to say that years pass, the heroes age and you have a growing sense that the good times will come to an end. You might think that after 2000 pages you’d be glad to reach the end, but in fact you do feel a sense of loss when you finally reach it. Review: The Water Margin - A superb story of mankind in all its glory, explaining why, ultimately, man must end up an outlaw in the Water Margins if he is to survive with his honour intact. Women, bandits, bureaucrats, mothers-in-law, grandmothers, soldiers, policemen, children, the weather, nature (including tigers), combine to force man time-after-time to choose his destiny. the story follows the lives of countless people (mainly men) who are forced to choose, but always their characters are full and deep, not cartoon 2D, they and their enemies have a realism that is lost in Hollywood or airport blockbusters. what a pity the translation is at times banal, but for all that it is clear and simple prose and maybe the first Chinese book in which I have been able to read and actually follow the geography and history.

| Best Sellers Rank | 267,648 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) 19,621 in Literary Fiction (Books) |

| Customer reviews | 4.4 4.4 out of 5 stars (165) |

| Dimensions | 18 x 11.3 x 9.5 cm |

| Edition | New |

| ISBN-10 | 7119016628 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-7119016627 |

| Item weight | 1.36 kg |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 1642 pages |

| Publication date | 1 Jan. 1993 |

| Publisher | Foreign Languages Press, Beijing |

I**S

A lot more than a yarn about robbery with violence

Two things you notice about this novel are: first, you get four volumes totalling over 2100 pages in a slip case; second, each volume is perfectly sized for a laptop case or pocket or handbag. So, the formatting would have been perfect if I had still been commuting. As it was, I read all four volumes during the Co-vid lock down and semi-lock down, and had a wonderful sense of escapism, as I spent several weeks in 12th century China. Older readers might remember the TV series The Water Margin, which feels as if it was shot soon after Outlaws of the Marsh was written in the 14th century. The book is far longer and more complicated than the series, although this edition might still not give you the full monty. In the introduction, a professor of Chinese literature, Shi Changyu, explains that the novel exists in several different versions, varying between 70 and 124 chapters. This edition has 100 chapters, which might be a good compromise. At the end the translator, Sidney Shapiro, explains how he put this edition together, selecting bits from the short and long editions, and excluding some ridiculous poems that give away the plot. Shapiro himself was an American who lived in China for many years, married a Chinese woman and became a Chinese citizen in 1963, just in time for the Cultural Revolution. I wonder what Mao thought of this novel. The translation itself was made in the 1970s, and gives us a lively, colloquial read which “zips along” – just like a recent Booker Prize judge said novels ought to do. The text itself is an odd mixture of American and British grammar and spelling, with lots of typos, but that don’t detract from the enjoyment of the read. So, what’s it all about? The novel was written in the 14th century and is based on real events that occurred in the 12th century. In some ways it’s a kind of Robin Hood story. 108 men and women (if memory serves, 105 men and three women) are obliged, through a combination of injustice and misfortune, to betake themselves to Liangshan Marsh where they join a growing robber band that robs the rich and either gives to the poor or leaves the poor alone. The 108 chieftains (there are thousands of foot soldiers in the band) are all distinct characters, and along with their given name, they each have a moniker that reflects some feature of their history, physique or chosen weaponry. For instance, one of the female chieftains is called Ten Feet of Steel because she wields two swords, both five feet long, to deadly effect. The first couple of volumes tell the story of each of the chieftains and how they came to join the robber band. They spend a lot of time consuming vast quantities of wine (presumably rice wine) and meat in taverns that seem to be strewn around the countryside. It’s so easy to walk into a tavern and demand a bowl of wine and a platter of meat, but do you always know what you’re getting? There are a lot of rascally inn-keepers who drug their guests and then take them to an abattoir round the back of the tavern where they chop them up and cook them in pies which they serve the next set of guests. No food safety standards in 12th century China. Eventually the emperor realises that the bandits are a potential force for good and after a couple of attempts to offer them an amnesty are thwarted by evil, envious officials, they go mainstream and are used to fight against neighbouring kingdoms. Warning: there is a lot of violence throughout the novel, but it often feels like cartoon violence. Lots of heads are chopped off and bodies salami-sliced, but there is little graphic description and most of the victims are nasty people who deserve a bit of rough justice. There is enough moral philosophy around to raise this novel above a mere adventure yarn, with frequent references to Buddhism, Taoism, filial piety and the sanctity of friendship and oaths. Another warning, which is stated in the introduction, is that women do not get a good press here. Apart from the female chieftains (and they’re not really central characters) most of the female characters are grasping wives who cheat on their husbands, bawds who facilitate adultery or ale-wives who drug their guests and bake them in pies. I won’t spoil the ending. Suffice to say that years pass, the heroes age and you have a growing sense that the good times will come to an end. You might think that after 2000 pages you’d be glad to reach the end, but in fact you do feel a sense of loss when you finally reach it.

H**U

The Water Margin

A superb story of mankind in all its glory, explaining why, ultimately, man must end up an outlaw in the Water Margins if he is to survive with his honour intact. Women, bandits, bureaucrats, mothers-in-law, grandmothers, soldiers, policemen, children, the weather, nature (including tigers), combine to force man time-after-time to choose his destiny. the story follows the lives of countless people (mainly men) who are forced to choose, but always their characters are full and deep, not cartoon 2D, they and their enemies have a realism that is lost in Hollywood or airport blockbusters. what a pity the translation is at times banal, but for all that it is clear and simple prose and maybe the first Chinese book in which I have been able to read and actually follow the geography and history.

V**J

A classic and well translated read

Growing up in a Chinese household, it is quite common for me to hear several folklores and the 108 outlaws was one of them. When I saw this, I immediately bought it and I got what I paid for. A classic read with several nice illustrations that helps me in getting to know the story more. Overall a great read, with good translation from Chinese to English

E**D

A moral Quest Against Tyranny and Injustice.

It's an old story,as old as the History of Mankind itself,the moral right of the outcast,of the disspossed to assert their identity and freedom against tyranical opression of the overlord.How many times has the world witnessed such events since and will witness again in the future,war and conflict seem to be the continueing legacy of humankind. I enjoyed the translation by Sidney shapiro,who brings to it a depth and insight of someone well aquainted with the Chinese cultural legacy,while at the same time sifting the psychological nuances that clarify the translation as a whole.

M**R

One of the world's great folk-novels, but the translation is problematic

Outlaws of the Marsh, better known to British audiences as 'the Water Margin', after the popular Japanese series shown on BBC in the 1970s, is one of the four great classical Chinese novels, and a masterpiece of folk-tale in novel form. It catalogues the complex and sometimes seemingly haphazard adventures of a group of bandits who join together in the Liang Shang marshes, resisting the cruelty of Gao Qiu during the Song dynasty. This is an enormously engrossing read, with a compelling chapter to chapter progression which it makes it very hard to put the books down. By turns comic, tragic, thrilling, base and noble, this is a book that really does have something for everyone. There are three problems for Western readers coming to this novel through this translation. First, the moral background to this novel is entirely different from anything in Western literature. This was rather sanitised for the TV series, which prefaces every episode with 'in a world very different from our own', and casts the whole thing as rebellion against injustice. The novel, however, is altogether more difficult. Sometimes things are done to resist oppression, sometimes they are done out of filial loyalty, sometimes for revenge, sometimes because people are drunk, and sometimes with no more justification than that the perpetrators are bandits, and therefore have a right to do such things. At times the author appeals to the moral indignation of the reader, but at other times he glosses over atrocities which go as far as cannibalism. Most modern readers will also have questions about the casual mistreatment of women throughout the novel, by both sides. Secondly, with more than 150 characters, and four densely printed volumes, there is an awful lot of this to read and follow. Readers who are well-used to Chinese names will struggle less with this, but just keeping track of who is who is quite an undertaking. The episodic structure also picks up a character for a few chapters and then leaves him behind. This is not a flaw in the writing -- rather, it's a different approach to storytelling and the novel from the one we are used to, though readers of medieval literature will find it more familiar. Finally, the translation is not entirely complete. The purpose of translation should be to render the original accurately into the new language so that it sounds as though it had been written in that language. Sidney Shapiro, a Chinese-naturalised Jewish-American scholar, does not quite achieve this. Somehow the style of writing is all mixed up, bringing epic words such as 'in twain' next to 'ass-hole', and riper language. On the other hand, Chinese scholars consider this to be much more accurate than Pearl Buck's hugely popular 1933 version entitled 'All Men are Brothers'. Rather than seeing 'Outlaws of the Marsh' as a bad translation, it is probably best to see it as incompletely edited. The translation is also not helped by the print production, which has several typographical errors on each page, thanks to poor proof-reading by the Beijing Foreign Language Press. Interestingly, Outlaws of the Marsh was Mao Ze Dong's favourite novel, and he considered it the inspiration for a number of his military strategies. Five stars for the novel, then, less half a star for the translation and another half for the print. Outlaws of the Marsh would be on my list of '100 novels translated into English that ought to be read', both for its own sake, and for its cultural importance.

J**H

Der originale Text erschien auf der Website des Webmagazins "Comicgate" in der Kategorie "Währenddessen." Der über zweitausend Seite schwere Roman "Outlaws of the Marsh" von Shi Nai‘an und/oder Luo Guanzhong, war letztes Jahr ein Mammutleseprojekt. Das Buch gilt neben "Journey To The West" und "Romance Of The Three Kingdoms" als ein chinesischer Klassiker. "Outlaws Of the Marsh" erzählt die Geschichte von 108 Gesetzlosen, die im Liangshan-Distrikt ihr Lager aufschlagen und von dort aus Angst und Schrecken verbreiten. Zunächst kämpfen sie gegen die Truppen des Kaisers, danach wehren sie fast im Alleingang eine Invasion der Tataren ab. Über eintausend Seiten erzählt der Roman zunächst, wie diese Gruppe zusammenkommt und rollt detailliert die Biografien der wichtigsten Charaktere auf. Das ist für mich der spannendste Teil des Romans, da diese Episoden nicht nur sehr unterhaltsam sind, sondern sich auch mit Fragen über das Böse beschäftigen. Ist es zum Beispiel böse, den Mord seines Bruders zu rächen, da es gegen das Gesetz verstößt, Selbstjustiz zu üben – oder ist es die einzige Form wahrer Gerechtigkeit, die man vollstrecken kann? Können böse Buben wie der Schwarze Wirbelwind, eine der Hauptfiguren des Buches, auch Gutes vollbringen, solange er nur von den richtigen Leuten angeleitet wird? Oder bleibt er nur ein gewalttätiger Schläger, der mehr als einmal im Jähzorn Leute sehr detailliert verstümmelt? Das sind die spannenden Fragen des Romans und die erste Hälfte wurde ich gut unterhalten. Aber dann beginnt die erwähnte Invasion der Tataren und aus einem Buch mit vielen Grauzonen, wird ein klassisches Narrativ von Gut gegen Böse. Die Räuber werden auf einmal von einer Liebe zur Heimat erfüllt – sie haben sich ja stets nur gegen korrupte Minister und nicht gegen das Reich aufgelehnt – und vermöbeln die Invasoren. Das passt wohl zu den historischen Hintergründen des Romans und ich kann mir vorstellen, dass die Autoren das einbauen mussten, um kaiserlicher Zensur zu entgehen, aber schade ist es trotzdem. Davon abgesehen bietet der Roman viele Actionszenen wie aus einem Wuxia-Film: tränenreiche Schwüre der Bruderschaft, wahre Freundschaft und einen bizarren Running-Gag. Denn sehr oft passiert einer Figur, dass sie in einem Gasthaus halt machen und der Wirt plant, diesen umzubringen. Scheinbar sind alle Gastwirte im Reich schäbige Diebe und Mörder. Die Hauptfigur kriegt das raus, es wird sich geprügelt und dann stellt sich heraus, dass der Wirt einen Freund der Figur kennt, den er sehr vergöttert und warum hat die Figur das denn nicht gleich gesagt – man ist ja schließlich Teil derselben Bruderschaft und einen werten Miträuber tötet man schließlich nicht. Schön zu wissen, dass es doch so was wie Ehre unter Dieben gibt. Ich hatte wirklich gehofft, dass "Outlaws of the Marsh" einer meiner liebsten Romane werden würde. Die allzu patriotische, zweite Hälfte hat das aber zunichte gemacht. Was soll‘s. Die erste Hälfte ist ja noch da.

L**A

Pictures: 1: Volumes two and three, still in shrink-wrap. 2: Volume one, with jacket removed (the damage to the lower corner was caused by me after purchase) 3: Volume one, open. I won't dwell much on the novel itself, as it's a classic. I will say, however, that this is the first Chinese novel I've read, and I thought at first it might be a slog, considering its age and extreme length. I was pleasantly surprised to find, however, that it is actually quite accessible and action-packed, even funny at times. While the novel is long, the chapters are quite short, making it easier to get through. As of Chapter 12, the flow is definitely weird compared to Western novels; rather than having a single focused plot, it's almost like a relay race, where you'll have a few chapters following character A, who then meets character B, then a few chapters following them, and so on, except that major characters do tend to show up again later. From what I've heard, these strands do eventually converge later on. There are also a lot of extraneous details that would be omitted in a more streamlined modern novel. The hardest thing, for many monolingual English readers, will be keeping up with the hundreds of Chinese names, which because of the nature Chinese phonetics (especially when stripped of tones), and the small number of Chinese surnames, can tend to sound alike. It just takes some getting used to. The translation is quite good, and not overly pedantic the way these things can be sometimes. I do feel it would benefit from a bit more in the way of cultural and linguistic footnotes, especially for those who aren't knowledgeable about Chinese culture, religion, etc. But if anything, despite the translator's warnings in the introduction about alien cultural practices, it's actually surprisingly universal and relatable, compared to some of the weirder parts of, say, the Bible. I was quite satisfied with the volume itself, and I definitely think it's worth spending the extra money to get this over the paperback version. The Foreign Languages Press is an official press of the Chinese government, so this is comparable to something like a Library of America edition. It's sturdy, attractive, and should last a long time.

E**C

I love the book. The translation is fair. I especially like the size of the books, great for reading pretty much anywhere.

M**S

Good edition - but I'm no academic in the subject. Won't bore you paraphrasing other complimentary reviews. Highly recommended

R**L

A obra é ótima, mas veio avariada na caixa. Não devolvi porque a chance de troca é zero e os livros vieram inteiros.

Trustpilot

1 week ago

2 weeks ago